Miracles & Massacres

A most anxious day. I think we are getting it in the neck.

The concerns of Travis Hampson, a physician from Birmingham General Hospital serving behind the front line in the Royal Army Medical Corps, were well-founded. Although he hadn't seen any fighting first-hand, the relentless and unforgiving march south from Mons to the outskirts of Paris over the previous twelve days betrayed to Hampson (and to every other man in khaki) that the British and French armies were struggling to contain the massed advance of over one and a half million German troops. Rapid rifle fire wasn't enough to deal with the sheer weight of numbers in every enemy attack, and units were woefully under-equipped with machine-guns. They'd inflicted a bloody nose or two on the Kaiser's men, but the Germans were now just one decisive battle away from capturing Paris, and Britain's entire military participation in the war was hanging by a thread.

When they were packed off to war a month earlier, the mission of the British Expeditionary Force was to assist French forces where needed; orders from Whitehall were to avoid becoming embroiled in an attritional struggle with the German Army which would inevitably bleed the BEF dry. However, they'd ended up bearing the brunt of the German advance, and had quite literally been decimated as a result. More British soldiers had died in a fortnight than were killed in action during three whole years of the Boer War; an utterly unprecedented loss of life. After the mauling at Le Cateau, the majority of the BEF withdrew to the rear, leaving the French to hold the front line, and "contingency options" were quietly explored. There was really only one contingency option which held any weight - an all-out British retreat to the Channel ports, and subsequent evacuation back to England, effectively abandoning France to fend for itself - and the decision on whether to do this lay, ultimately, with the army's commander-in-chief.

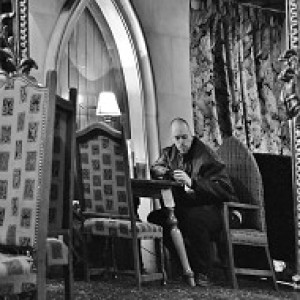

The popular stereotype of high-ranking officers during the First World War is encapsulated by Geoffrey Palmer's portrayal of Douglas Haig in Blackadder Goes Forth, as he sweeps countless toy soldiers off a model battlefield before tossing them absent-mindedly into the nearest bin. But for Field Marshal Sir John French, commander of the BEF during 1914 and 1915, nothing could have been further from the truth. An emotional and temperamental man, popular with the public from his Boer War days and even known to shed tears in front of his men - a rare thing in any military, but frankly astonishing in the "stiff upper lip" culture of the British Army - French was a gifted military thinker with no taste for industrial slaughter. In years gone by, he'd habitually adopted the affectations of enlisted men, rolling his shirt sleeves and smoking a briar pipe, and was always delighted to be mistaken for an ordinary Tommy. His affection for the common soldier made him reluctant to waste their lives, and in turn, he was a far more popular figure among the Tommies than any of his peers and eventual successors (though this popularity came at the cost of strained relations with Lord Kitchener and many others in the government). Having spent most of his army career in the cavalry, he was also blindly devoted to the idea that mounted troops would still be relevant in 20th century warfare, stubbornly formulating plans for the strategic use of horses at the front even as machine-guns cut them down. Field Marshal French was, ultimately, a nineteenth century soldier appalled and perhaps even scared at the unfolding horrors of the new war. And in September 1914, he was presented with an unenviable dilemma: to end the British Army's participation in the war, betraying an ally but saving the lives of his men, or to honour the Entente and risk the annihilation of his entire army in the process.

His mind was finally made up on the 5th of September 1914. A few stern communications from Lord Kitchener and at least one impassioned plea by French general Joseph Joffre probably swayed him, but more tantalisingly, the chance had arisen to deliver a truly old-fashioned, decisive blow against the German Army along the River Marne. France was almost ready for a full-scale counter-attack, and the Germans had left their right flank perilously exposed; they could be surprised, encircled, enveloped. It was a plan which appealed to Field Marshal French, and so for the first time since mid-August, the British Army prepared to advance.

The subsequent First Battle of the Marne was both a miracle and a massacre. While the British Expeditionary Force drove virtually unopposed between two German armies, creating absolute chaos in the enemy lines, French reinforcements were ferried to the front line from Paris by hundreds of the city's Renault taxis, a colossal joint undertaking between civilians and the military which transformed French pride and morale overnight. And yet, the last battle of the war to be fought in open countryside proved a charnel house for soldiers at the mercy of artillery and machine-guns; of two million men who fought on the Marne, half a million became casualties. Sergeant Thomas Painting of the King's Royal Rifle Corps recalled an entire battalion of elite German jagers surrendering at Hautevesnes, unwilling to lift their heads to shoot amid the hail of metal in the air. In spite of the carnage, Painter described a sense of elation at realising that "the Germans were not going to get their way."

Because the Marne was also the death of Germany's plan to capture Paris and force an early end to the war. In fact, if the British and French commanders had only realised just how devastating their initial breakthrough was (when he realised the full extent of the catastrophe facing his reeling forces, German general Helmuth von Moltke actually suffered a nervous breakdown), they could have inflicted a crushing defeat which may have ended the war early on terms favourable to the Entente. But some quick thinking by German officers enabled the defeated armies to retreat and regroup on the River Aisne some thirty miles to the north, where they immediately began to dig a complex system of interconnected trenches and saps stretching for hundreds of miles across the front. The war would not be won by Christmas. The British Army would not be going home. Battles would no longer hinge on movement and grand tactics, but on technological innovation and bloody attrition.

The course of the next four years was largely decided that day in September 1914, and few who fought on the Marne would live to see the madness to its conclusion.

- 0

- 0

- Nikon D3100

- 1/33

- f/5.3

- 42mm

- 800

Comments

Sign in or get an account to comment.